Working as a product designer in a cross-functional team is like being part of an intricate dance. The choreography involves developers, product managers, marketers, and other stakeholders, each playing their part in harmony to bring a vision to life. The product design role is unique; you’re not just a participant, you’re also a bridge, connecting different parts of the team to create cohesive and impactful products.

Over the years, I’ve learned that thriving in this environment requires a blend of skills, mindset, and a touch of humility. Here are the attributes that I believe are most important and the strategies that have worked for me throughout my career.

1. Empathy: The Cornerstone of Collaboration

Empathy is at the heart of good design, but it’s equally critical in team dynamics. Understanding your teammates' goals, challenges, and perspectives fosters trust and smoother collaboration. Developers might prioritize feasibility and efficiency, while marketers are focused on positioning and user acquisition. By empathizing with their priorities, you can frame your design decisions in ways that resonate with their goals, bridging gaps and aligning everyone towards a common vision.

2. Clear and Frequent Communication

When working in a cross-functional team, clarity is king. Ambiguities can lead to misaligned expectations and, ultimately, frustration. Early in my career, I learned the power of over-communicating. Share updates regularly, clarify your design rationale, and ask for feedback often. Tools like Slack, Figma, and collaborative documents have become my best friends for staying transparent and accessible.

3. Adaptability: Embracing Change

Cross-functional teams are dynamic by nature. Priorities shift, timelines compress, and requirements evolve. As a designer, being flexible and maintaining a problem-solving mindset helps you stay effective. I’ve found it useful to frame changes as opportunities to refine and improve rather than setbacks.

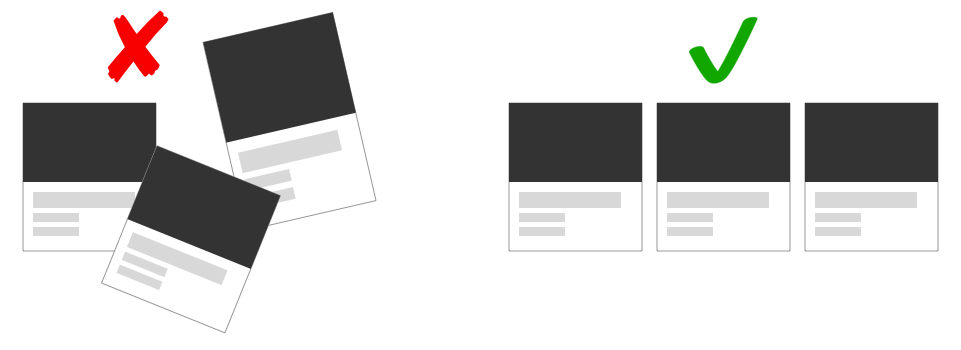

4. Collaboration Over Ownership

While you might take pride in your craft, it’s crucial to remember that products are built collectively. It is common for designers early in their career to feel protective of their work, but embracing diverse perspectives will almost always strengthen the final product.

5. Being an Advocate for the User

In the whirlwind of deadlines and business goals, it’s easy for user needs to get overshadowed. As a designer, you’re the voice of the user. Anchoring discussions around user feedback and usability testing results ensures the team’s decisions are rooted in real needs, not assumptions. Balancing this advocacy with team goals—without becoming overly dogmatic—is an art worth mastering.

What’s Worked for Me

1. Starting With a Shared Vision

One of the most valuable lessons I’ve learned is the importance of aligning on goals from the start. Kickoff meetings where the entire team agrees on objectives, user pain points, and success metrics set the tone for collaboration. When everyone is on the same page, it’s easier to navigate conflicts and stay focused.

2. Building Relationships

Work isn’t just about deliverables; it’s about people. Taking the time to understand your teammates as individuals—their working styles, preferences, and even hobbies—builds rapport and makes collaboration more enjoyable. A developer who knows you appreciate their effort is more likely to go the extra mile for your design.

3. Iterating Together

Collaboration doesn’t end with handing off designs. Working closely with developers during implementation ensures that the final product aligns with the vision. Addressing questions in real time and being open to tweaks during development have been game-changers for me.

Final Thoughts

Working as a product designer in a cross-functional team can be challenging, but it’s also deeply rewarding. The interplay of diverse expertise leads to richer solutions than any of us could create alone. By promoting empathy, communication, adaptability, and a collaborative spirit, you not only contribute to great products but also grow as a professional.

Remember: the best outcomes happen when the team’s success takes precedence over individual contributions. When you focus on building trust, fostering open dialogue, and championing the user, you’ll find yourself thriving in the intricate dance of cross-functional collaboration.